Isaiah 60:1-6

Ephesians 3:1-12

Matthew 2:1-12

Psalm 72:1-7,10-14

The Feast of the Epiphany (January 6th) is one of those relatively rare days in the Christian year when the Gospel reading is always the same. The reason is very simple. Although this has long been a major feast of the Church -- and of special importance in the Eastern Orthodox tradition -- only Matthew makes any mention of the strange event on which it is based -- the arrival at the stable of strangers from some far off place. Tradition has filled out the story considerably, notably by holding that there were three travellers, identifying them as 'kings', and even giving them names. The Bible does not provide any basis for this. In some modern translations the description 'wise men' is rendered 'astrologers', and in fact 'magicians' may be the most accurate-- which reduces their status considerably for a modern audience.

So why has this brief and mysterious episode attracted so much attention for so long? The answer lies in the theological significance that has been found in it. First, the fact that the travellers seek out Herod, but then fail to report back to him, gives an early sign of the 'political' context in which Jesus was born -- the actual Messiah ultimately proves quite at odds with what people hoped for or (in the case of Herod) feared. Secondly, the gifts that the wise men leave in the stable all have symbolic meaning; gold and frankincense are traditional gifts for a king, but myrhh also presages death. Thirdly, these men are Gentiles, foreigners. This is the most important aspect. Although the story of the birth, ministry, suffering and death of Jesus has to remain firmly rooted in the Jewish theology of a long expected Messiah if it is to be understood properly, it has significance far beyond the confines of Jewish life and culture. The Gospel is a Gospel for Jew and Gentile. This is St Paul's great insight, an insight that leads him, at intense personal cost, to take on the enormous task of proclaiming a Jewish Gospel to a Gentile world -- a call that he explicitly acknowledges, appropriately, in the Epistle for Epiphany.

'Epiphanic moments' are those times when, quite suddenly, something of the greatest imortance strikes us. At the Feast of the Epiphany we commemorate and celebrate the moment at which the universal importance of the Jewish religion is, for the first time, revealed to the whole world. It is the moment, we might say, when the birth of the historical Jesus is revealed to be the incarnation of the eternal Christ.

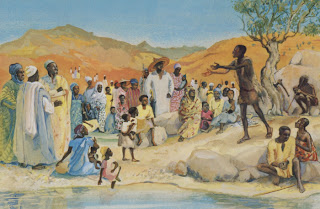

The Magi by He Qi -- courtesy of Jean andAlexander Heard Library

This blog offers a short reflection on Bible readings in the Revised Common Lectionary (RCL) for Sundays and major Christian festivals throughout the year.

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

Friday, December 24, 2010

The Holy Innocents

Jeremiah 31:15-17

Revelation 21:1-7

Matthew 2:13-18

Psalm 124

Revelation 21:1-7

Matthew 2:13-18

Psalm 124

|

| The Slaughter of the Holy Innocents |

The commemoration of the Holy Innocents – the children exterminated by Herod in his furious determination to eliminate any possible rival to his throne -- is not widely observed in the life of the Church. No doubt this is because it falls on Dec 28, just three days after Christmas. Yet for centuries it has been a “Red Letter” day, which is to say, a major festival of the Christian year. The children who died were probably few in number – Bethlehem was a small place, after all – and could know nothing of the reasons for the ghastly fate that befell them. Nonetheless they traditionally count as martyrs – not just because of their innocence – but because they died for the sake of Jesus.

The politics of Palestine at the time of Jesus made an explosive mixture. Herod’s position as a Jewish king serving a Roman Empire deeply at odds with Judaism inclined him to the kind of brutal “realism” that so readily regards the innocent as expendable. “Messiahs” were cropping up all the time, and the movements they prompted were generally crushed mercilessly. He was not to know that the Messiah who had just been born sought a wholly different type of kingdom, one so different that it could best be described as ‘not of this world’.

The astonishing level of sheer cruelty that was inflicted on the mothers and children of Bethlehem is still with us. The tyrannical exercise of political power reached unprecedented heights in the 20th century, and does not show much sign of receding in this one. Commemorating The Holy Innocents so close to Christmas serves as a helpful antidote to the saccharine sweet scenes in which the baby Jesus so often appears at this time of year. It reminds us that God did not come to dwell among us in a world of sleigh bells and festive fare, but to secure a victory on the Cross that, despite the suffering, sorrow and injustice described in the Gospel for today, enables us to keep faith with the vision of Revelation that provides the Epistle – ‘the first things have passed away’ and the God whose ‘home is among mortals’, has made us this promise "See, I am making all things new."

Monday, December 20, 2010

CHRISTMAS

Titus 3:4-7

Since many churches, perhaps most, have multiple services at Christmas, the Lectionary provides no fewer than three sets of readings – though the same set of readings is used in each year of the 3-year cycle. All three lists forge a connection between the prophet Isaiah and the birth of Jesus.

This connection is crucial to understanding the significance of that birth, as the Epistle readings extracted from Hebrews and Titus make clear. Thanks to modern scholarship, however, we now know something that the authors of those epistles did not know. The Book of Isaiah is really three books. Moreover, the authors of these three books (Chaps 1-39, 40-55 and 56-66) lived and wrote several hundred years apart – before, during and after the traumatic capture and exile of the Jew in Babylon.

The editing of these materials into “one” book is no accident. Whoever its editors were, they correctly perceived that the same spirit, and in large part the same theme, animates them all – how to have a faith that endures. This is what makes it possible for the Old Testament readings for Christmas to make a selection from all three. And this fact carries an important lesson for us. When John the Baptist asks Jesus if he is ‘the one who is to come’, he is making reference to a hope and a yearning that has persisted over a very long period of time, and across dramatically changing fortunes. We should take this timescale to heart.

“A thousand ages in Thy sight, are but an evening gone” Isaac Watts reminds us in his paraphrase of Psalm 90. It is easy for us to confine the advent of the Messiah to the deeply intriguing and appealing, but brief, event that is the Nativity. God’s saving work in his Messiah certainly began at Christmas, but the birth of Jesus was dimly recognized for what it was only thirty years later, after his death and Resurrection. And its full significance lies within the immensely vaster time scale of God’s redeeming history.

The key spiritual task at Christmas is to find a way of acknowledging that in Jesus God came to an earthly home, without at the same domesticating him. The deep innocence of Jesus that makes our redemption possible, is not that of a sweet little baby. “He came and dwelt among us” so that, for all our follies and weaknesses, we might be raised to God’s level, not that God might be reduced to ours.

Monday, December 13, 2010

ADVENT IV

|

| The anxieties of St Joseph -- James Tissot |

Romans 1:1-7

Matthew 1:18-25

Psalm 80:1-7, 16-18

The readings for this week form a bridge between Advent and Christmas. The Gospel begins the story of Christ’s Nativity which is about to unfold in longer readings on Christmas Eve, Christmas Day and then Epiphany. At the same time it looks back to the ancient promise of a Messiah, and directly quotes the prophet Isaiah in the famous passage that provides the Old Testament lesson for this Sunday

Since we are still in Advent, we have only the start of the story in brief. Yet this short passage does something very special -- it enables us, unusually, to focus on the distinctive role of Joseph in the Gospel of God. Since Jesus owes his humanity, as well as his Jewish identity, to his earthly mother Mary, she has had a widely acknowledged theological role in the mystery of the Incarnation. Yet in a quite different way, Joseph also has a key part to play in God’s salvation history, since he too could have accepted or rejected it.

Nowadays, single parents and unmarried mothers are a thoroughly familiar part of life. As a result, it takes real imaginative effort to appreciate the significance of Mary’s highly unorthodox pregnancy in a culture so different to our own. At the annunciation Mary memorably says ‘be it unto me according to your word’. The great courage and deep faith that this reveals, is matched by Joseph’s response, however. Confronted with such devastating news, it would be natural for anyone to feel an intense personal affront and rejection. But Joseph had to face this further prospect -- acute embarrassment, ridicule, and social contempt.

All the time he had at hand an easy as well as a socially approved solution – ‘to dismiss her quietly’. The angelic voice in the dream tells him to do otherwise, but it relies, of course, on his having the spiritual insight and moral courage to accept that advice. His reward is to be accorded parental status by being giving the task of naming the baby. As it turns out, this is no small reward. Paul declares to the Christians at Rome in this week’s Epistle that their whole calling – like ours – is ‘for the sake of that name’. And at the name of Jesus, he tells us elsewhere, every knee shall bow.

Monday, December 6, 2010

ADVENT III

‘What did you go out to look at?’ Jesus asks the crowd in this week’s Gospel, ‘A reed shaken in the wind?” It is an image that has caught the imagination, and provided books and poems, as well a sermons, with a striking title. But what exactly does it mean? The exchange occurs in a section of Matthew’s Gospel that is mostly about the significance of John the Baptist. Clearly, ordinary people were much struck by this extraordinary man, and here Jesus is prompting them to ask themselves why.

Some commentaries suggest that freak winds blowing the reeds around Galilee could be a remarkable sight. Surely the people didn’t go to see John as some kind of freak? But they can hardly have been drawn by his social stature. No one could have been less like the political dignitary who dresses in soft robes and lives in a royal palace. No they went to see a prophet. And that means, consciously or unconsciously, they went to see him out of spiritual longing.

This week’s Old Testament lesson is one of Isaiah's most famous passages, and one with which the crowd would have been thoroughly familiar. It gives graphic expression to that longing “Then shall the eyes of the blind be opened, and the ears of the deaf unstopped, the lame shall leap like a deer and the tongue of the speechless sing for joy’. John is the harbinger of this vision, Jesus its fulfillment. The fulfillment is not all sweetness and light, however. ‘Here is your God, come with vengeance, and terrible recompense’.

Once again, the themes of the first and second comings are interwoven. The First Coming of carols, social festivities, and the baby in the manger falls easily within our comfort zone. We know what to expect, and we like what we know. The Second Coming when (as the Epistle puts it) ‘the Judge is standing at the doors!’ is a much more strange affair, and inevitably generates a mixture of personal anxiety and spiritual incomprehension.

Advent is the opportunity to switch these around – to find the Incarnation spiritually awakening, precisely because divine judgment on the lives we lead is what it is reasonable to expect.

Monday, November 29, 2010

ADVENT II 2010

|

| John the Baptist preaching in the desert |

Isaiah 11:1-10

Romans 15:4-13

Matthew 3:1-12

Psalm 72:1-7, 18-19

The traditional color for the Season of Advent is purple. Increasingly, however, blue is used as an alternative, and this reflects a significant change in thinking, a change embodied in the Revised Common Lectionary. In part Advent is like Lent – a penitential season when our thoughts should be focused on the great, but awesome, themes of sin and redemption. In Cranmer’s original Book of Common Prayer, and in the versions that followed for many centuries, the Sunday lessons throughout Advent had the “Last Things” as their unifying theme – death, judgment and the Second Coming of Christ.

In the Revised Common Lectionary, by contrast, on the last Sunday in Advent we switch from death to birth, when the Gospel of the day begins the Christmas story. This is not mere convenience. This year’s Gospel for the second Sunday of Advent demonstrates just how closely the Second Coming and the First are connected. John the Baptist, warns his hearers of judgment in the sternest language -- "You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come?” – and he urges them to repent because “the kingdom of God is at hand”. This is the stuff of the Second Coming and of old-style Advent. But then, almost immediately, he turns their attention to the First Coming when he tells them that “one who is more powerful than I is coming after me”.

The fact is, God’s time is not our time. Strictly, in the eternal God there is neither ‘before’ nor ‘after’. Incarnation and Judgment are two sides of a single divine act. The ‘baby in the manger’ is at one and very the same time ‘Christ in his glorious majesty’. The trouble, though, is that we have become so comfortable with the homely image of the baby, we need several weeks to remind us that his coming is a challenge to much that we hold dear.

John cautions his hearers against spiritual complacency – “Do not presume to say to yourselves, `We have Abraham as our ancestor'; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham”. As Christmas approaches, this message is apposite for us too. God doesn’t need us; we need God.

Wednesday, November 24, 2010

St Andrews Day

November 30 |

Romans 10:8b-18

Matthew 4:18-22

Psalm 19 or 19:1-6

St Andrew was one of the disciples expressly called by Jesus. The Gospel for his feast day is brief, and recounts his call. Little else is known of him, but this is distinction enough. A fisherman like Peter, he appears in just a few Gospel episodes, and does not seem to have been one of the 'inner circle' of disciples -- Peter, John and James. Yet the image of the simple peasant fisherman, who, despite his lack of education, could recognize the extraordinary presence of Jesus, has commanded respect and veneration in countless times and places. Here is someone with whom the least ambitious of Christians can identify.His is a role that any of us can be called to fulfill. In the Epistle set for his feast day Paul says "How are they [the mass of humanity] to call on one in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in one of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone to proclaim him?" The message is simple. People can't know about Jesus until someone tells them. Furthermore, those who are ignorant might include our nearest and dearest. Andrew stands out because he was instrumental in the call his own brother. Ever since, he has represented the humble folks who lead people more charismatic and energetic than themselves to the service of Christ. In this way he offers us a suitably modest Christian ambition -- to be mere conveyors of the message of salvation in Christ, yet conveying it in the expectation, and the hope, that those to whom we carry it will make a far bigger impact than we ourselves ever could. Such is the satisfaction of belonging to something vastly greater than ourselves -- 'the communion of saints'.

St Andrew is the patron saint of both Scotland and Russia. In their radically different ways, the religious traditions of these two countries -- Calvinism and Eastern Orthodoxy -- show how evangelism can take quite different forms and yet to equally powerful effect.

Tuesday, November 23, 2010

ADVENT SUNDAY 2010

A note on the Readings for the first Sunday in Advent 28th November 2010

by Gordon Graham

Romans 13:11-14

Matthew 24:36-44

Psalm 122

On Advent Sunday we begin a new cycle of readings. This year the Gospel passages (for the most part) come from Matthew rather than Luke, from which they were taken over the course of last year. But on Advent Sunday itself, the change is not so very significant. Whatever the year, this week’s readings are always powerfully apocalyptic – all about the end of time and the final judgment.

The modern world, I guess, has greater difficulty in believing in an apocalyptic end to time than people had in centuries past, and ‘adventism’ is generally regarded as somewhat extreme by the members of mainline churches Yet, there they are – readings from OUR Bible, appointed to be read this Sunday by OUR lectionary. So what should we think about them? How are they best understood?

The first point to emphasize is that, despite the frequency with which people have tried to predict ‘the end of time’, in Matthew’s Gospel Jesus is quite clear -- “about that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father”. In other words, all this will happen in God’s time, not ours. Secondly, ‘if the owner of the house had known in what part of the night the thief was coming, he would have stayed awake and would not have let his house be broken into’. Each of us has our own ‘end of time’ – the hour of our death. It does not matter when God brings the whole of history to a close if we have met the end of own lives unprepared.

Suppose with the inevitability of death in mind, we take the message of Advent to heart? What then are we to do by way of preparation? The Epistle for this week has the answer ‘You know what time it is now, how it is the moment for you to wake from sleep. Let us then lay aside the works of darkness and put on the armor of light; let us live honorably as in the day’. The passage from Isaiah puts it even more simply ‘Come, let us walk in the light of the LORD!’ The ‘moment’ to make this choice is now.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)